WebRTC is cool. WebRTC is hard. WebRTC is painful, actually. Partly due to how alien the API feels, partly due to many tutorials skipping a lot of the details. Here’s my attempt at describing WebRTC and how I used it for some fun Comlink experiments.

Update 2017-11-06: I updated the section about gathering ICE candidates.

There couldn’t possibly be a TL;DR for WebRTC. But here’s a fun demo.

The problem with many existing WebRTC introductions

There’s a good amount of WebRTC introductions and tutorials out there, but they all seem to follow a similar pattern:

- Be handwavey about the inner workings of WebRTC and what the APIs data structures hold.

- Show how to open a data connection within the same page.

- Drop in some copy-and-paste backend code and provide STUN/TURN server URLs.

- Use

getUserMedia()to build your own Skype.

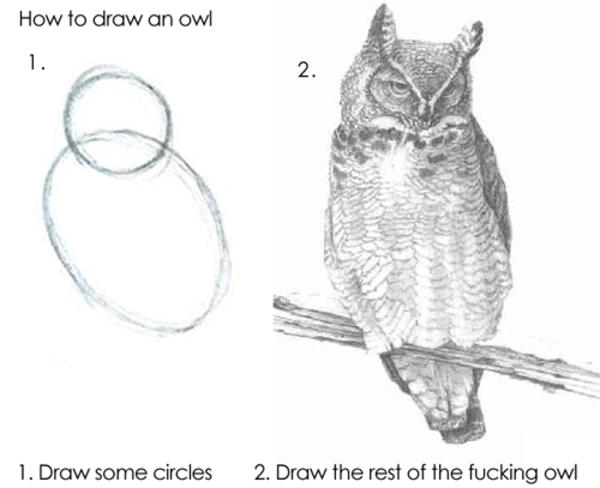

It’s the WebRTC version of “How to draw an owl”:

In my opinion, there’s a multitude of drawbacks with this approach to teaching WebRTC. First of all: WebRTC is about creating peer-to-peer connections on the web. There’s no reason to consistently conflate WebRTC with the Media API. While I do understand that one of the main motivations behind WebRTC was telecommunications/teleconferencing on the web, only presenting WebRTC and Media API in tandem adds a lot of cognitive load if you are not intimately familiar with getUserMedia(). It makes it harder for the reader to see where WebRTC’s responsibilities end and Media API’s responsibilities start. And you need all the cognitive capacity you can muster because I have to say that WebRTC is one of the weirder APIs; one of those APIs that stand out because they are not very intuitive to a web developer. It takes energy not to get mad, but it’s what we got. So buckle in, let’s make it work.

Note: I will skip some details in my code snippets on this blog post. The full length code can be found in my demo.

WebRTC

The one end of the connection

Everything starts with an RTCPeerConnection.

const connection = new RTCPeerConnection();

This is already a bit weird. We don’t have a connection to anyone, but we do have a connection instance. The next weird thing is that we need to create the channels we want to use later, so we create our data and video channels before an actual connection has been established. This is necessary so WebRTC can properly negotiate what kind of connection to set up. In our case we are looking to create an RTCDataChannel so we can exchange simple text messages between peers:

const channel = new Promise(resolve => {

const c =

connection.createDataChannel('somename');

c.onopen = ({target}) => {

if (target.readyState === 'open')

resolve(c);

};

});

This is a little pattern I started using to make it easy to await values. It creates a promise that resolves once the data channel has been successfully opened.

Note: WebRTC has lots of more features and events you should usually consider for a production-level app like handling reconnects, handling more than one remote peer and more. I am ignoring all that here. lolz.

WebRTC now knows what kind of connection we want, but to whom? To connect to another peer we need to tell them who and where we are, what we can do and what we expect. Additionally, we need to know the same from our remote peer. In WebRTC, part of this data is encapsulated in the RTCSessionDescription. Session descriptions come in two flavors: “Offers” and “Answers”. Both flavors contain mostly the same data like codecs, a password and other metadata. They seem to only differ in who gets to be the connection initiator (that’s the answer) and who is the passive listener (that’s the offer). As the the name implies we can’t start with creating an “answer”, so we start with an “offer”:

const offer =

new RTCSessionDescription(await connection.createOffer());

Note: In Chrome both

createOffer()andcreateAnswer()returns a promise that resolves to anRTCSessionDescription. In Safari Tech Preview and Firefox it resolves to a JSON object that needs to be passed to theRTCSessionDescriptionconstructor.

Now we need to tell the connection instance that we are using this end of the connection. Why? I don’t know, who else would own this end of the connection? Oh well, here goes:

connection.setLocalDescription(offer);

connection.onicecandidate = ({candidate}) => {

if (!candidate) return;

// collect `candidate` somewhere

};

connection.onicegatheringstatechange = _ => {

if (connection.iceGatheringState === 'complete') {

// We are done collecting candidates

}

}

Once we set our local description, we will be given one or more RTCIceCandidate objects. ICE or ”Interactive Connectivity Establishment” is a protocol to establish a connection to a peer in the most efficient way possible. Each RTCIceCandidate contains a network identity of the host machine along with port, transport protocol and other network details. Using those additional details the ICE protocol can figure out what the most efficient path to our remote peer will be.

Note: Most of the time a machine is not aware of it’s public IP address. For that you would need a STUN server (more below).

You will never know when you are done receiving candidates. There could always be a new one during the lifetime of your page: Think of someone opening your app and then dialing into the airport WiFi. You should always be ready to incorporate a new candidate. In my demo I cheated a bit: I just wait until there hasn’t been a new candidate for more than a second and declared that “good enough”.

You know you have received all the RTCIceCandidates when the connection’s iceGatheringState is set to "complete". Did I mention that WebRTC is weird? (Thanks to Philipp Hancke for correcting me on this.)

A backend appears (aka. “signalling”)

So what do we do with these ICE candidates? Well this is where I got really frustrated with the design of WebRTC: It is your job to get both the offer as well as all the candidates to your remote peer so they can configure their RTCPeerConnection appropriately. This process is called “signalling”.

Idea: I’d love for the Web to have a Peer Discovery API (or something) that allows me to find peers using local network broadcasting. Maybe it could even support Bluetooth networks. I think a game like SpaceTeam should be possible to be built on the web.

In my first ever WebRTC demo I didn’t want to write a backend so I just serialized both the offer and the array of candidates using their respective .toJSON() methods and made the user copy/paste the resulting string from a <textarea>. That works but is pretty cumbersome. For my new demo I wrote simple Node backend with a redis database to create a pseudo-RESTFul “rooms” API. Rooms are created with a name and have 2 slots. Each slot can be filled with a peer’s WebRTC data. Once both slots are filled, 2 people “are in a room”, can grab each the other peer’s session description and candidate list, clear the room and set up their connection. I won’t go into the implementation details of the backend, but the source is there for you to read — and it’s not even 50 lines!

With this backend in place, the first peer creates a room with a user-given name and uploads the offer and the candidates list to the room’s first slot. At this point this peer has to play the waiting game and wait for data to appear in the room’s second slot. It’s time for us to switch over to the other side and implement peer number two.

The other end of the connection

On the other side we start the exact same way as with peer number one: By creating a RTCPeerConnection. But this time we want to wait for a data channel to appear. Additionally we want to create an answer, for which we first need to get ahold of the offer! So we need to hit the backend, check the room’s first slot to get the the peer’s data and apply it to the connection:

const connection = new RTCPeerConnection();

const channel = new Promise(resolve => {

connection.ondatachannel =

({channel}) => resolve(channel);

});

const {offer, remoteIceCandidates} =

await getDataFromRoomSlot(roomName, 1);

connection.setRemoteDescription(offer);

for(const candidate of remoteIceCandidates)

connection.addIceCandidate(candidate);

At this point this end of the connection knows how to connect to the first peer (provided there is a way to connect). You’d think we could go ahead and just send our data to the other peer using this knowledge, but WebRTC wouldn‘t be WebRTC if didn’t have to do the entire dance in the other direction as well. So here goes: We have to create an answer and collect this end’s RTCIceCandidates as well and send them back to our first peer — again using our signalling backend.

const answer =

new RTCSessionDescription(await connection.createAnswer());

connection.setLocalDescription(answer);

connection.onicecandidate = ({candidate}) => {

if (!candidate) return;

// collect all `candidate`s in an array

};

connection.onicegatheringstatechange = _ => {

if (connection.iceGatheringState === 'complete') {

// done collecting candidates

}

}

await putDataIntoRoomSlot([answer, allIceCandidates], roomName, 2);

Back to the first peer

Meanwhile the first peer has been patiently polling for data to appear in the second slot of our room. Once it does, we do the same as our second peer:

const {offer, remoteIceCandidates} =

await getDataFromBackend(roomName);

connection.setRemoteDescription(offer);

for(const candidate of remoteIceCandidates)

connection.addIceCandidate(candidate);

At this point our RTCPeerConnection is exactly that, a proper connection! 🎉 You can see why most tutorials start with creating a connection within the same page as it allows them to skip the backend and just pass the offer and the answer directly to both ends of the connection. But we want the real deal, and we felt the pain, didn’t we? Now that our connection is established, we don‘t need our backend anymore(!!). Our channel promise should resolve and we can actually start transferring data. We can send buffers or strings using send() and listen to incoming messages using onmessage on that channel object.

Firewalls? NAT?

What if the peers can’t connect? If the peers are not on the same network, they won’t be able to connect without some extra help. The first measure is a so-called STUN server. A STUN server’s only job is to tell you what your public IP is in a WebRTC-compatible manner. In 99% of cases that will solve the connection issues. STUN servers are cheap to run and as a result there’s a good amount of free STUN servers for you to use.

However, if there is a firewall in place, you need more heavy machinery: A TURN server. The “R” in TURN stands for “Relay”, because it relays your data in your stead. This way WebRTC can work even with firewalled networks at the cost of having to tunnel the entire session’s traffic through this relay server. Because most WebRTC applications are built to do some sort of teleconferencing with video streaming, running a TURN server can become quite expensive due to the amount of traffic.

I didn’t set up a TURN server for my experiments so I have no experience to offer (ha!) on this end. There is an old but still valid guide by my colleague Sam Dutton.

WebRTC: Recap

The WebRTC bit of this blog post is done. We have have a data channel that allows us to send data from one peer to another without routing it through a remote server. WebRTC is quite the ride and you have to do a lot of things in exactly the right order to get where you want to end up — but once you are there you have some very interesting capabilities at your disposal to build powerful web apps.

Comlink Shenanigans

What is Comlink?

Comlink is my most recent pet project. At it‘s core it’s an RPC library. It’s was extracted from the polyfill I wrote for my tasklets proposal. It’s purpose is to expose JavaScript values to remote JavaScript environments as if they were local values. The canonical example is a website that creates a worker. Comlink allows you to use the values of the “remote” worker environment as if they were part of your main thread JavaScript scope. Here’s a code snippet that will hopefully make it clear:

<-- index.html -->

<!doctype html>

<script src="../../dist/comlink.global.js"></script>

<script>

const worker = new Worker('worker.js');

// WebWorkers use `postMessage` and therefore work with Comlink.

const api = Comlink.proxy(worker);

async function init() {

// Note the usage of `await`:

const app = await new api.App();

alert(`Counter: ${await app.count}`);

await app.inc();

alert(`Counter: ${await app.count}`);

};

init();

</script>

// worker.js

importScripts('../dist/comlink.global.js');

class App {

constructor() {

this._counter = 0;

}

get count() {

return this._counter;

}

inc() {

this._counter++;

}

}

Comlink.expose({App}, self);

As you can see, even though the App class is defined in a different scope (and in a different thread, even!), I can access it from my website’s JavaScript environment through Comlink. That instance I create is also in the worker context, which is why all operations are implicitly async-ified (yes, that’s a word).

Comlink works with everything that uses postMessage, so it can work between pages and workers, pages and serviceworkers, workers and serviceworkers, iframes, windows — you name it!

WebRTC + Comlink = 💖?

Here’s where I got my idea: The send() method of the RTCPeerConnection is very close to a postMessage() interface. If I could make Comlink work with a RTCPeerConnection I could expose values from one machine to another. There’s only two things missing:

send()is string-based whilepostMessage()can send proper JavaScript objects. So I’ll have to callJSON.stringify()myself.postMessage()can transferMessagePorts to create new side channels. I’ll have to implement that myself.

MessageChannelAdapter

It turns out that similar string-based communication channels are used for WebSockets and the Presentation API. So it seemed worth my while to write a module that takes send()-like APIs and turns them into a postMessage()-like API with support for transferring MessagePorts. I won‘t explain the implementation but if you fancy take a look at the Comlink repository. There you can can find the MessageChannelAdapter.ts module.

Exposing window

Here’s the bit where I started to go a bit a crazy and push the limits. I exposed an object that contained three functions:

changeBackgroundColor: A function that takes anr,gandbvalue to change the background colorlog: Theconsole.logfunctiongetWindow: A function that will return a proxy to thewindowobject. With this, you have access to everything.document? Check. Globals? Check.eval()? Check.

const exposedThing = {

changeBackgroundColor: (r, g, b) => {

document.body.style.backgroundColor = `rgb(${r}, ${g}, ${b})`;

},

log: console.log.bind(console),

getWindow: _ => Comlink.proxyValue(window),

};

const channel = await createChannelUsingWebRTC(roomname);

const comlinkChannel = MessageChannelAdapter.wrap(channel);

Comlink.expose(exposedThing, comlinkChannel);

The other end can now use exposedThing as if it was a local value. They can change the pages background color by calling changeBackgroundColor, they can call log and make things appear in the other browser’s DevTools. They can even change the pages title using (await getWindow()).document.title and many other variants. See the video at the start of the blogpost above for a demonstration.

End of the line

At this point I’m gonna call it a day. The reason why I went on this journey is because I think this has the ability to spark many new ideas for things that could be done on the Web. Technically, this has all been possible on the Web for years, but the added developer convenience of Comlink will probably allow many more creative people to venture into this area of peer-to-peer programming. I could see this being used for game development, for more convenient API design and many other applications. I’d love to hear your ideas! If you have any or have any other remarks, hit me up on Twitter!